Hands down–this will be my least favorite post. I’m not a military or war buff. I even hate reading about it. I put off this post for a bit because I knew it wouldn’t be fun to write. However, despite how awful one might feel in response to the horrific events in history, it is important to see and learn in order to understand and grow. As appalling as it sounds, the suburban city of Hiroshima is a “tourist attraction” because it was the first city to be nuked by an atomic bomb. The absolute must-see places are the Peace Memorial Park and Museum, where one can dive deep into the history of Hiroshima: how it birthed into an industrial city and a key strategic military port that eventually led to its tragic destruction.

I’ll begin with the fun stuff first. Chris rode the shinkansen for the first time for our journey from Tokyo to Hiroshima, the fastest network of high-speed railways in Japan. Some trains can even reach up to 200mph! The shinkansen is highly more comfortable and convenient (and sometimes even more expensive) than traveling by air.

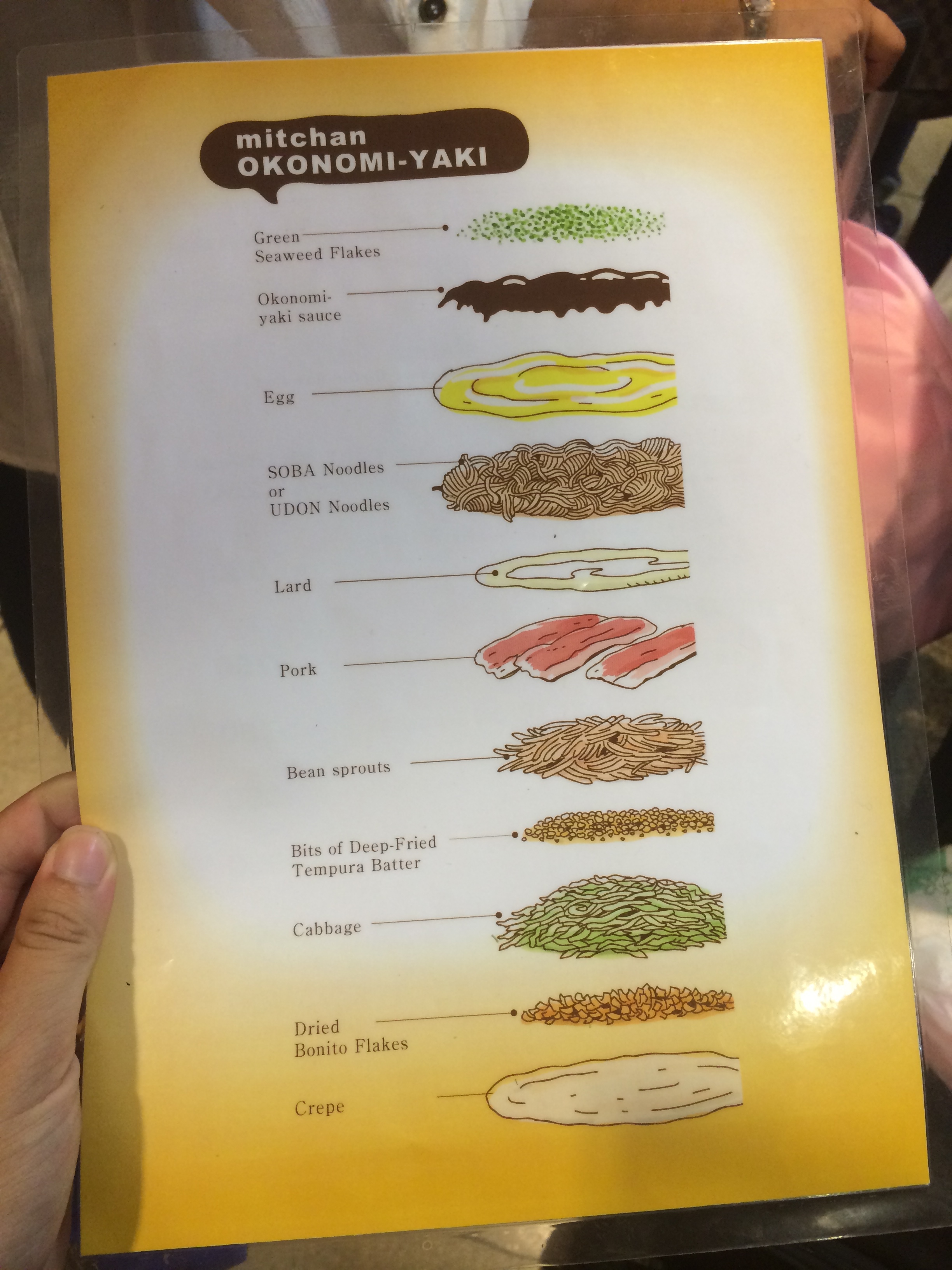

The “must eat” cuisines in Hiroshima consist of okonomiyake and tsukemen. I was never fond of okonomiyake, but I gave it another shot. We both agreed that the flavors were too strong for our liking, and I probably won’t be trying it again.

Tsukemen was so delightfully scrumptious, we ate it for dinner and again for lunch the next day. It is a “refreshing” dish to ramen: a plate of cold noodles, boiled cabbage, cucumber, green onions, and chashu pork is served with a bowl of sesame-covered spicy broth.

You dip the cold cuts and noodles into the spicy sauce and chow down!

We spent a day and a half in Hiroshima. To our surprise, our first full day began on August 3, 2014, exactly sixty-nine years after the U.S. selected Hiroshima out of three other cities for the atomic bomb. Now every year on the anniversary of the tragic day of August 6, thousands of people gather at this park for the Peace Memorial Ceremony. A myriad of chairs were already set up for the ceremony, covering the lawns of the park.

Though the exterior of the museum was quite an eyesore, the inner walls and displays provided in-depth information about the history of Hiroshima from its rise to its downfall, and its restoration.

The first floor beautifully illustrated the history of the city in the late 1800s, describing the major ports and railroads that were constructed during this time. Further along the timeline, light is shed upon the brutality of Japanese reign during their era of imperialism: the invasion of Manchuria, the Nanking Massacre in China, the occupation of Korea, the First and Second Sino-Japanese wars, and the surprise attack on the U.S. at Pearl Harbor. As Japan sank deeper into war, Hiroshima (along with most of the cities in Japan) became the grounds for military support; men were taught to fight, children were given jobs to destroy old buildings to create fire lanes, and women became factory workers and nurses.

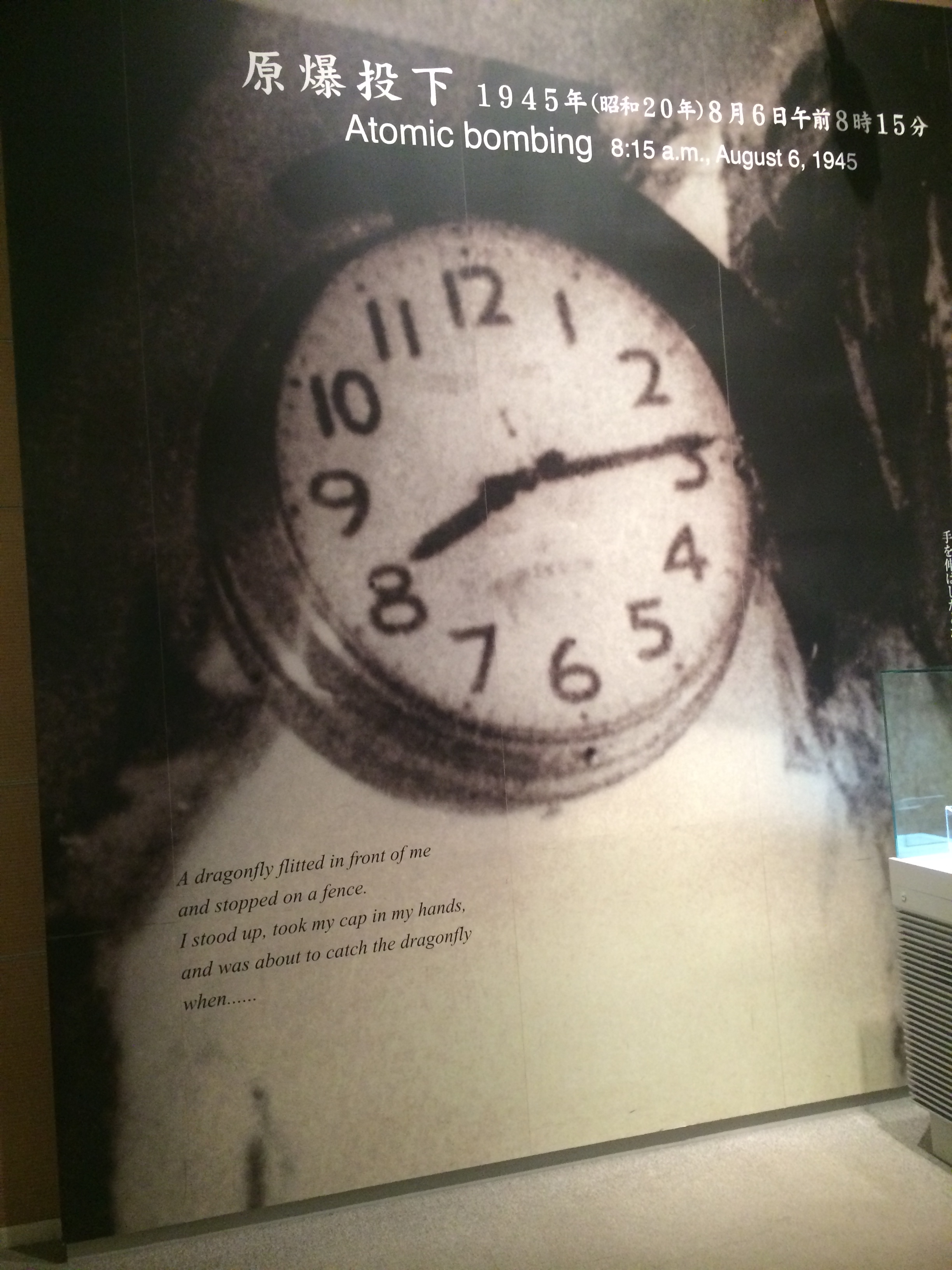

The second floor was reserved for information on the U.S. post Pearl Harbor: it presented exquisitely detailed information regarding the intelligence of its military, the secret WWII atomic bomb research and development project known as the Manhattan project, the first atomic bomb test in New Mexico, copies of letters between the president, military leaders, and scientists, and the details leading up to the decision of Hiroshima being the selected target. Of the four cities that were selected, Hiroshima became the final target because it was confirmed that it had no prisoners of war. It was on this floor where I learned the true definition of unconditional surrender. Previously, I thought the term “unconditional surrender” was a simple, “I give up! You win!” Boy, was I wrong. Understanding its definition helped me better understand why the Japanese were as determined and unwilling to surrender as they were. It was decided on August 3, 1945 that the U.S. would drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later on August 6, 1945 at 8:15am, it happened.

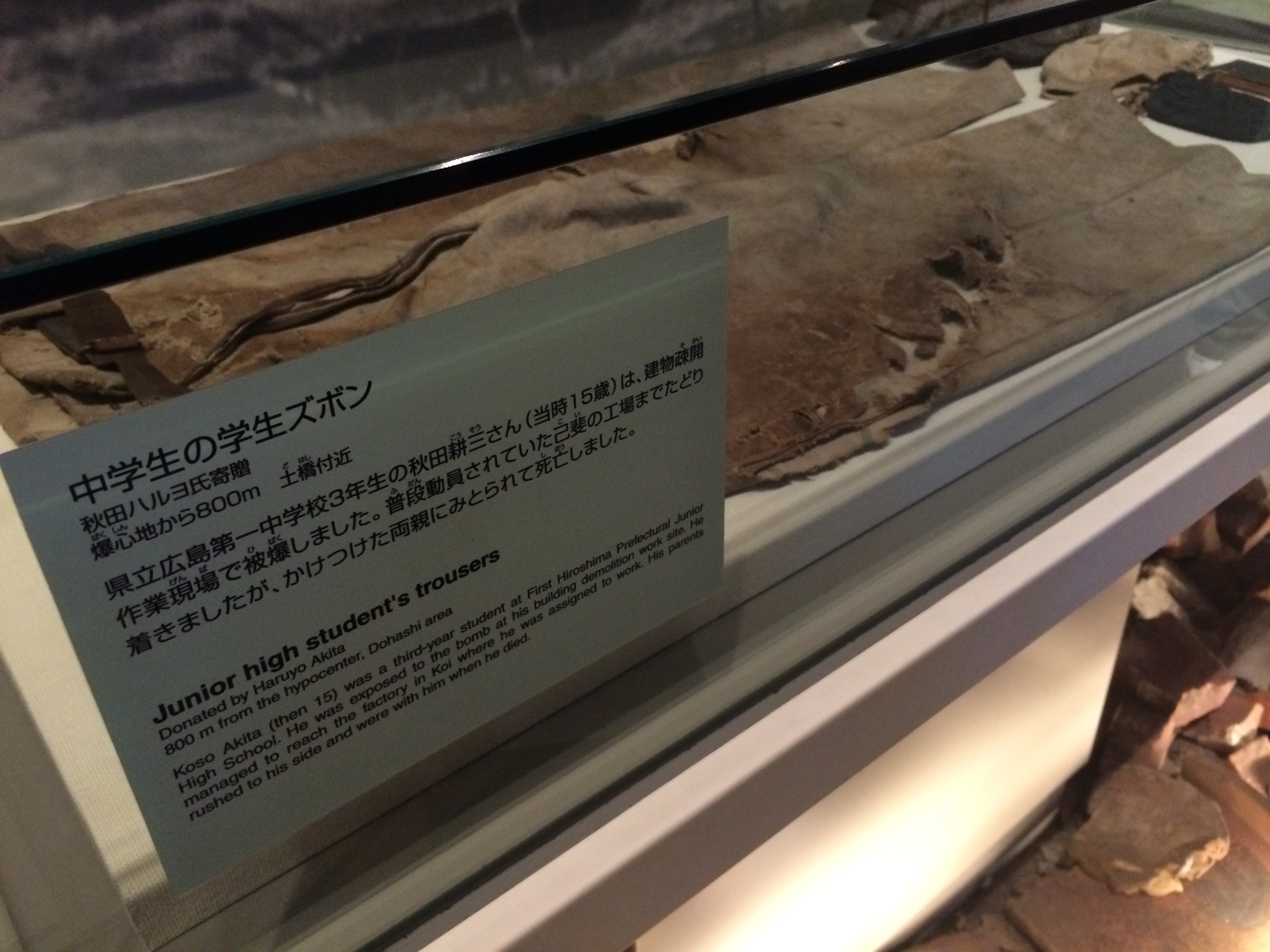

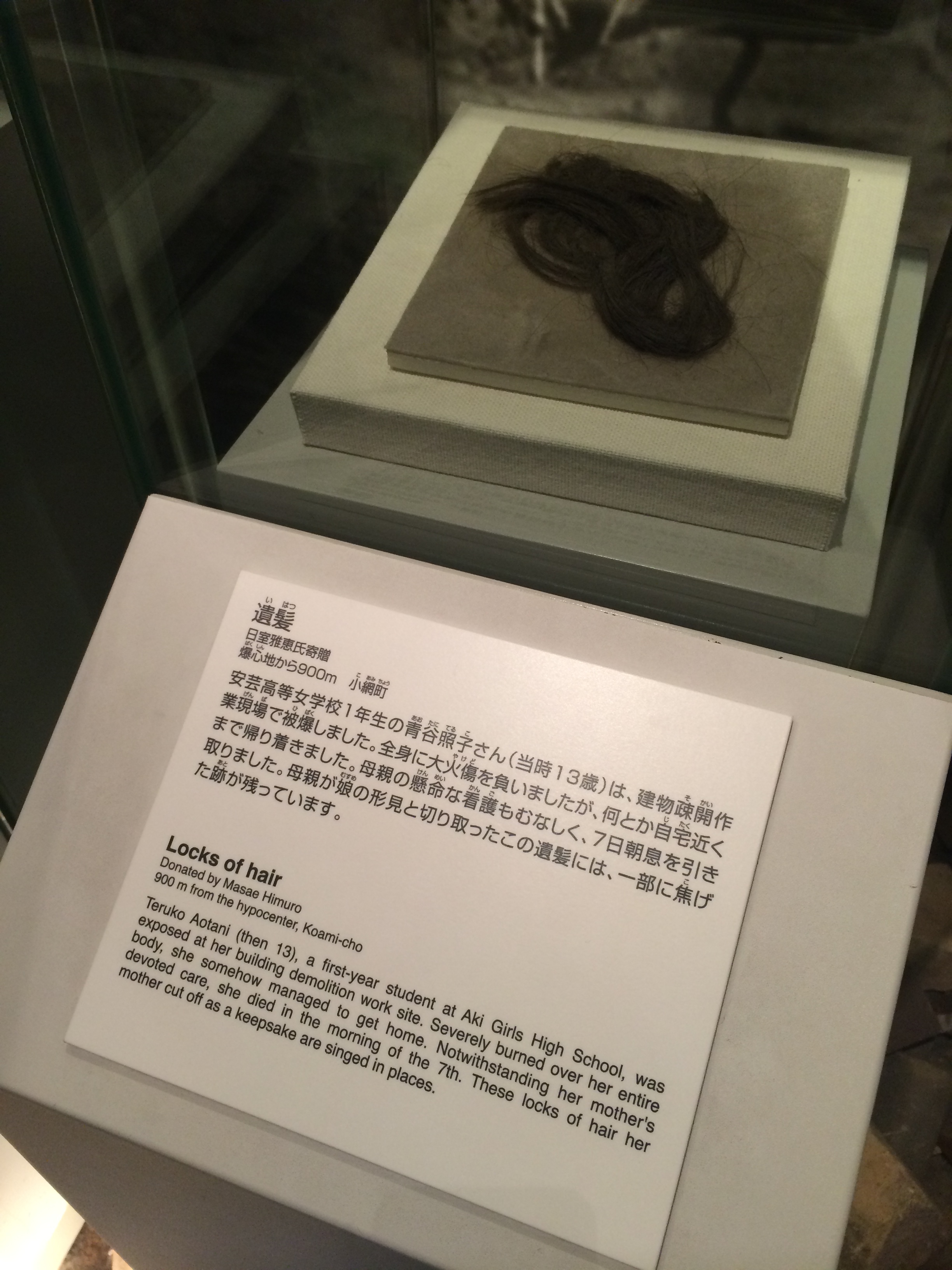

The third floor described the day of the bombing, its aftermath, and its toll on society today. Quotes, maps, and 3D city displays showcased the scale of the city, the size of the bomb, and where it was detonated. There was also a section on radiation and its causes and effects on the human body. This floor was the most heartbreaking floor, portraying graphic images of victims dead and alive, and actual artifacts from that horrific day.

Toward the end of the visit, the messaging on the museum walls campaigned for world peace and the Japanese desire to eliminate all nuclear weapons. Charts were presented, showcasing all the countries that had either signed or not signed treaties prohibiting the use of nuclear weapons. There were also maps depicting the amount of nuclear weapons that a number of countries possess (with the U.S. being #1). Every year the mayor of Hiroshima sends a telegram to leaders of countries that conduct nuclear tests to protest, and copies of these telegrams are displayed on numerous walls. Their advocation for the abolishment of nuclear weapons continues to persist today.

The two hours I spent at the Peace Memorial Museum taught me more about the history of August 6, 1945 more than any U.S. history class has ever taught me. The majority of the opinions I hear about this event (both in Japan and the U.S.) tend to oppose what the U.S. had done at 8:15 that morning. “What the U.S. did was just too much,” I often hear. Having not completely understood the history leading up to the events, I had no opinion. I do now. With the definition of “unconditional surrender” now understood, it’s much easier for me to understand why the Japanese persisted, despite the weakening of their country post Pearl Harbor. What really hits it home for me is the fact that they refused to surrender even after what happened on August 6. If they refused to surrender, even after all that, what would it have taken? A second attack. And even after Nagasaki was nuked, a military coup almost broke out in Japan when the emperor considered accepting the unconditional surrender. Due to their culture of dying in honor for one’s country, the military absolutely did not want to surrender even after the second atomic bomb! (I’m leaving out the Russian involvement immediately after Nagasaki, as that’s opening a new can of worms.) If the first A-bomb couldn’t secure an unconditional surrender from Japan, what would it have taken?

With those thoughts in mind, we exited the museum and strolled through the remainder of the park.

We sauntered over to the A-bomb dome, the only remaining building near the hypocenter of the blast. Although the glass dome had shattered to smithereens, the building remained quite intact, because the force of the blast came from almost directly above instead of from the side. As the city was rebuilt, it was initially easier to leave this building than it was to destroy it, and now it is preserved and remains as a historic sight.

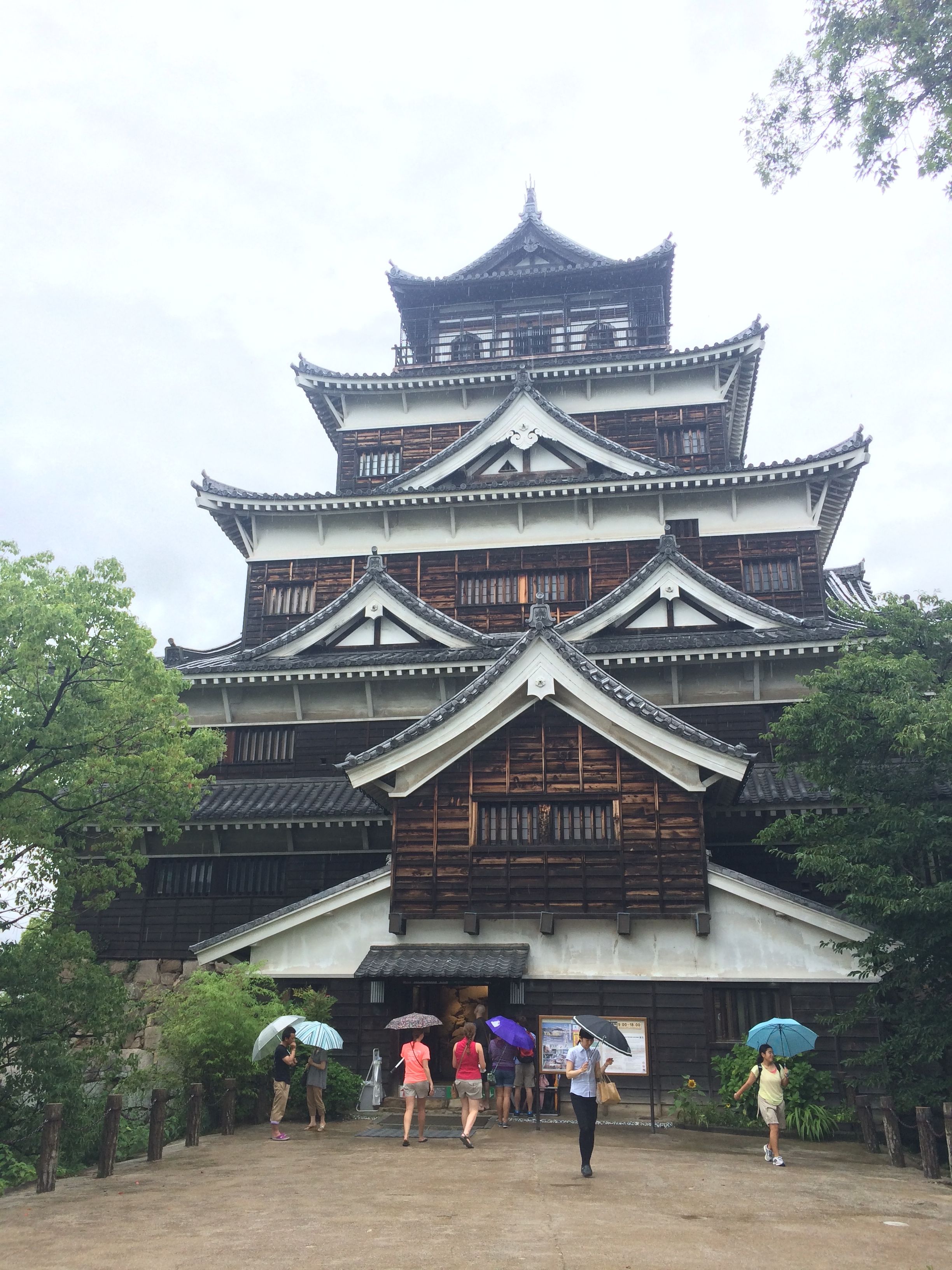

For a bit of decompression, we continued on over to the Hiroshima Castle. It was…boring.

But we enjoyed our stroll through the pristine gardens of Shukkeien.

Despite this being my third visit to Japan, it was my first visit to Hiroshima. I didn’t even know Hiroshima would be on the list of destinations until the week before! Albeit a sobering experience, a visit to Hiroshima and the Peace Memorial Museum is absolutely worthwhile; the studies of a country’s culture and history is equally if not more important than the travels there itself.

Pingback: Miyajima | Romping & Nguyening