It really wasn’t until Santiago de Cuba when we finally got a feel for the real Cuba. Not because the city seems to see fewer tourists than Havana, or because its cultural influences come from primarily Jamaica, Haiti, and Africa, or because its revolutionary history has helped influence Cuba’s music, art, architecture, and politics.

Around the charming plaza:

The busy streets of Santiago:

Like in Havana, it was refreshing to see children and teens playing soccer barefoot in the streets at dusk.

By the time we arrived to Santiago, we had finally begun to understand the gist of Cuba after having spent one week there. We even got to hang out with some chess players at the park. Chris got his ass kicked in chess by a chess teacher.

Twice for dinner we found a friendly lady selling food from her own house at national prices. At La China (across from the tourist restaurant La Juliana) we found yummy dinners for $30-50 CUP ($1.20-$2 USD). We laughed when a guy from La Juliana told us we were not allowed to eat there because we were not locals, and then proceeded to tell more lies in hope that we would go to his restaurant. The woman from La China quickly sat us down on rocking chairs in her living room and turned on the fans and television, treating us like family.

Figuring out things the local way became easier, which resulted in more local experiences. And that is not always a good thing.

Bits of frustration and shock occurred here and there up to this point, but not to the degree of fury and heartbreak we felt in Santiago. Let me first explain logistics. If at any point you need to figure out logistics in Cuba, give yourself at least half a day to plan and prepare because the country is full of inefficiencies and bureaucratic nonsense. Here, I gave Cuba its true name: Queue-ba.

Purchasing Domestic Plane Tickets in Cuba

After the delayed 14-hour bus ride from Trinidad to Santiago de Cuba, we knew we wanted to return to Havana by plane instead of by bus again. Also, we wanted to fly from Baracoa, our final destination and next point of interest after Santiago, back to Havana. For whatever reason, we quickly learned that it was not possible to purchase plane tickets from another city; plane tickets could only be purchased from your current city. The problem was that everyone advises against going into Baracoa without a bus or plane ticket out; departures from Baracoa are often sold out. We decided we would take a bus back to Santiago from Baracoa, and then fly to Havana from Santiago. Problem solved? No. Not even close.

We walked into the Cubana Airline office (which had a long queue outside) to inquire about plane tickets from Santiago to Havana. Before bothering to look up anything, the woman at the information desk told us that everything was completely booked all week and the following week to Havana. Baffled, we walked down the street to Etecsa, Cuba’s telephone and internet company, where we were able to purchase a $2 1-hour internet card without any complications or hassles. And to our surprise, internet was decent! We spent the next half hour searching for available flights on every airline in Cuba. Everything was sold out…only we later found that none of their websites worked. (We searched for dates 6 months in advance only to get the same results.) After the futile attempt of searching for flights online, we went to the tour agency Cubatur. For $135 each we were easily able to book flights on Cubana from Santiago to Havana. They gave us vouchers, which we had to change into airline tickets at the Cubana Airlines office.

So back we went to Cubana, where we had to wait in line outside in the scorching heat. Once we were finally inside, the doorman handed us a number and told us to listen for our number. Problem was no one was calling numbers. When we returned to the same lady at the information desk who had told us everything was booked, she smiled and said, “Good, you found tickets!” After waiting for a long, unknown period of time, I noticed that everyone else who had been in line after us had already left. Confused and frustrated, we asked around what the fuck was going on and why no one was calling numbers. Turns out that the Cuban way of queuing is finding el ultimo or the last person, keeping an eye on that person, and knowing to go immediately after the last person leaves. Luckily the locals were nice enough to let us go ahead, and even trading our vouchers for tickets was painfully slow, due to their antiquated computers.

After going to an airline office, telephone/internet office, tour office, back to the airline office, and several hours later, we got our plane tickets. Now that we confirmed our plane tickets, we needed bus tickets from Baracoa to Santiago. Because the Viazul office was nowhere near the center, we booked bus tickets online. Fortunately there were still tickets available because we were booking them a week in advance; every day before was completely sold out. Unfortunately an e-confirmation was not enough; a printed copy was required, and getting that printout is a story I will tell later in my next blog post.

Motorbike Rentals

The concept of renting a motorbike in Cuba is apparently like a lottery. The only company that rents motorbikes is Transtur/Cubacar and they suck. So hard. Lonely Planet says you can rent bikes from this company, but it doesn’t say that it’s a gamble and you’re better off not wasting your time.

We showed up at the office in the main center exactly at 1pm. They were closed. Their posted hours were 8-12 and 1-5. We grabbed a quick lunch and returned again at 1:45pm. Still closed. We returned again at 4:30pm and they were finally open, only to tell us we couldn’t rent motorbikes the next day or the following day. I was under the impression the boss was feeling lazy. So we walked to the only other Transtur/Cubacar office 2 km away, right next to Hotel Santiago. The rental car office was open, but the motorbike office was closed despite their sign saying they close at 8pm. Dude from the rental car company told us that as soon as they rent out all their bikes, they close up shop, and we should just return tomorrow between 9-9:30am. How people return their bikes, we do not know.

The next morning at 8am we decided to return to the first office because it was in town. Unsurprisingly the boss didn’t show up until 9:05. One guy returned his motorbike, but the boss told us he had no bikes for rent. He got on the phone with the other office near Hotel Santiago, and then told us to go to that office. We paid the rip-off $3 cab ride to the other office, only to be told that they didn’t have any bikes. We asked if we could reserve one for the next day, and he said it was possible. He wrote down our casa phone number, and said he would give us a call before 10am to let us know whether or not we could rent one. Why he couldn’t tell us this beforehand to save us the cab ride there, we do not know. And of course, we never got the call.

El Morro

Our plan with the motorbike was to ride out to La Gran Piedra and Valle Historico, but since we could not acquire a motorbike, we ended up with Plan B: a trip to El Morro, a fort/museum only 6 km outside of Santiago.

We hopped onto a truck from Plaza Marte for only $2 CUP each (8¢). For the first time we felt like cattle in a truck; sweaty, sticky bodies pressed against other sweaty, sticky bodies, skin on skin, standing and clutching onto bars and hoping we wouldn’t tumble over with each pothole in the road or abrupt stop. The tarp covering the truck protected our skin from the sun, but trapped the scorching heat and prevented any visibility. As I watched perspiration drip from faces and arms, I wondered just how long a short 6km could feel.

The truck finally arrived in Ciudamar, a short walk from El Morro. From there it was a beautiful stroll to the fort, where we observed locals enjoying their weekend with their families at the beaches.

El Morro, with a $4 entrance fee.

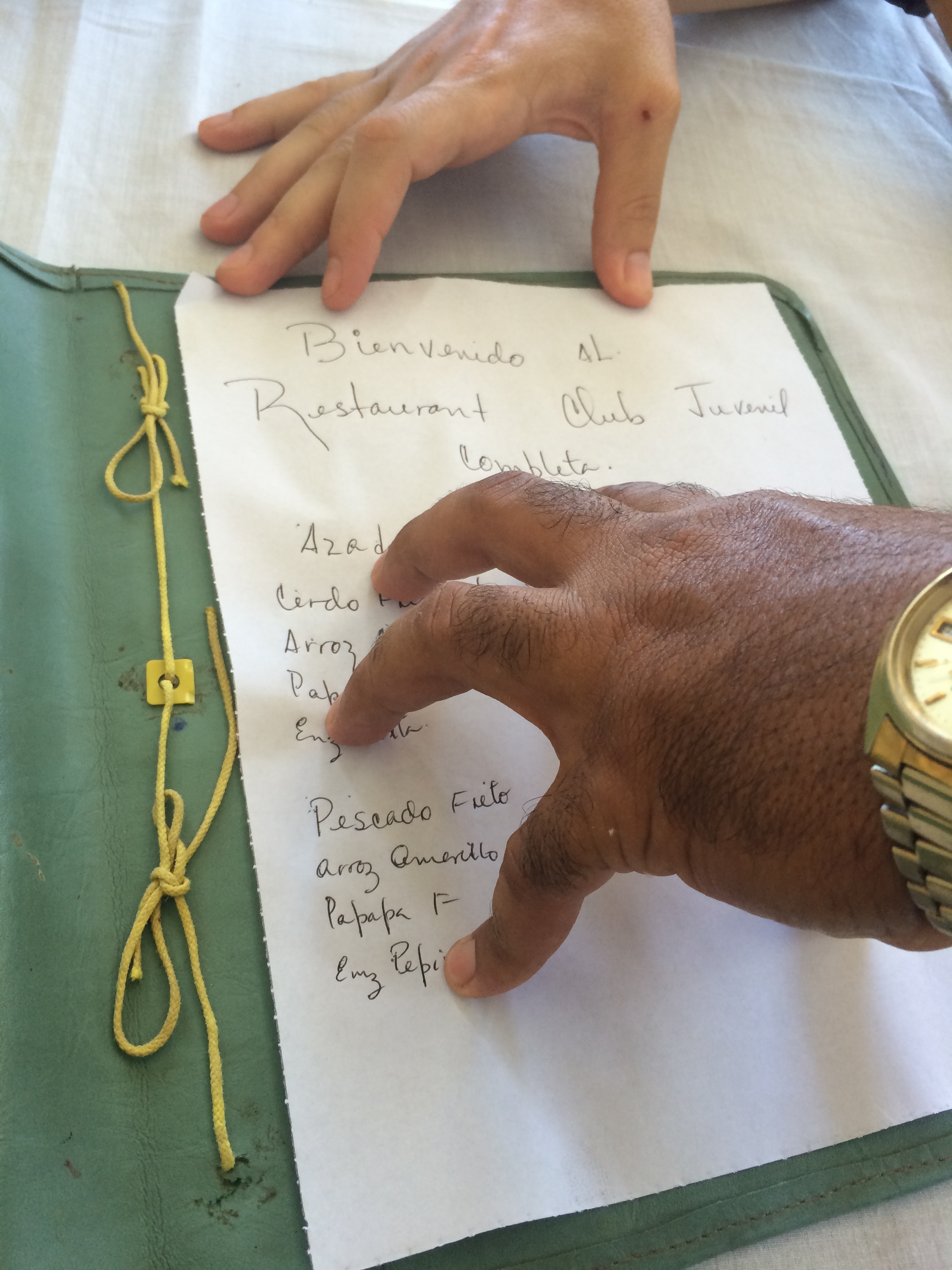

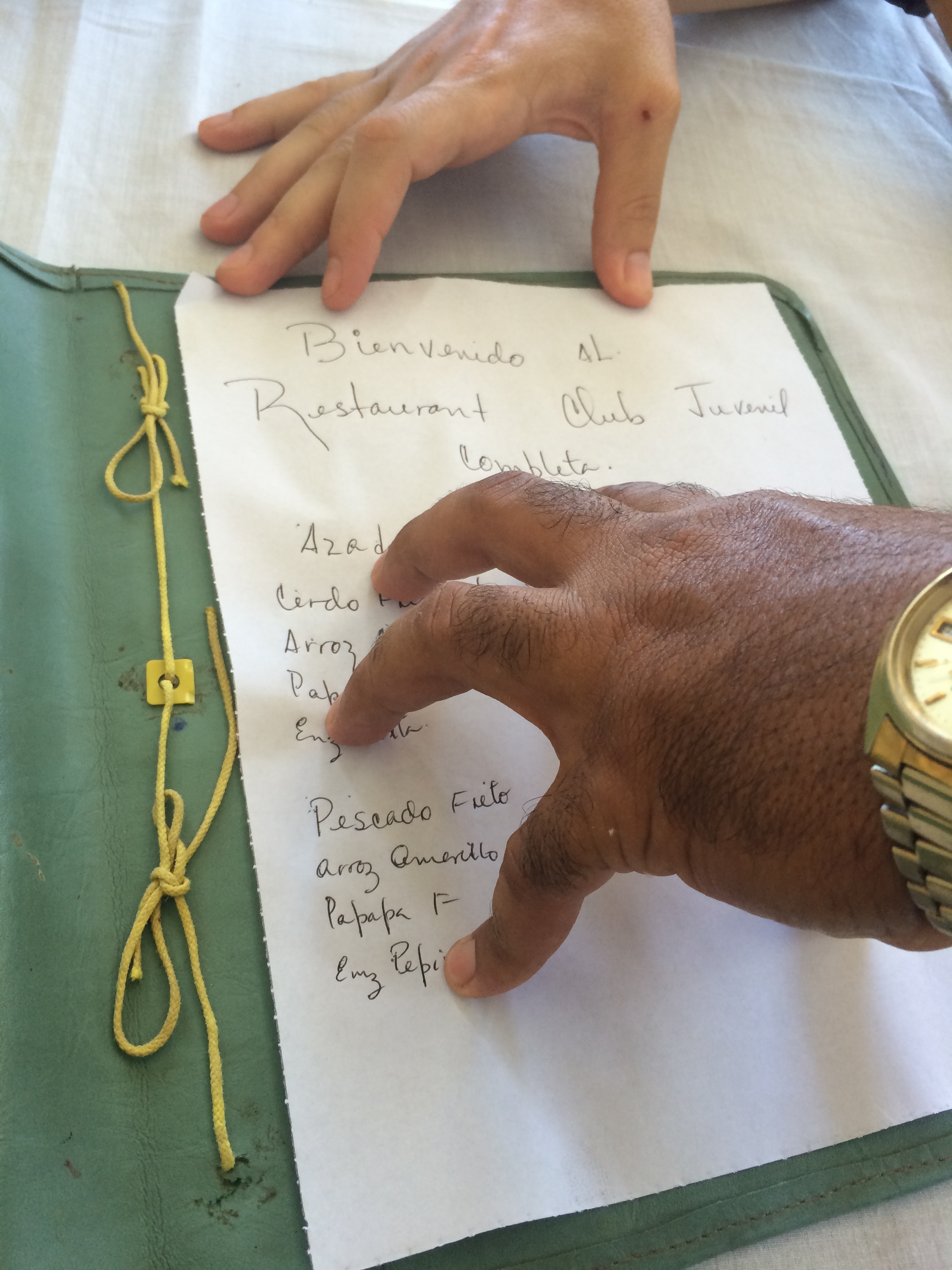

After El Morro it was time for lunch. Rather than spending money at the expensive, tourist-catered, cliff side restaurant at the fort, we opted to walk back to Ciudamar to have lunch at the cheaper, local restaurant. As soon as we stepped foot into the restaurant, the large, charismatic boss immediately told us it was $4 per person for lunch. However he then told other waitresses that it was $4 for us, which made us wonder, “If $4 is the normal price, why does he need to tell the waiters that it is $4?”

So I asked to see a menu. He sat us down at a table and disappeared for a while. A long while. When he reappeared he told us there was only one menu that was making the rounds and he would bring it to us as soon as it was available. And sure enough we got the menu. It was specially designed just for us, as it was handwritten on a blank sheet of paper. Chris and I stared at each other, too shocked to burst out laughing. I took out my camera and told the boss I wanted to take a photo of the menu, only to have him quickly cover the menu with his hand, claiming that he did not want other restaurants to know his prices.

There were no other food options around and we were starving, so we stuck around for the rip-off lunch. As we waited I asked the lady next to our table how much she paid for her lunch. She wouldn’t tell me. Everyone was playing the same damn game. At this point our rage and frustration grew stronger, and it felt as if it didn’t matter if we tried to experience Cuba the local way. In the end, no matter how hard we tried to avoid touristy, packaged experiences, we were going to be scammed, ripped off, and lied to no matter what. It was infuriating. But later that afternoon after a heart-to-heart conversation with a local, our fury softened into heartbreak and a deeper understanding of such deceitful behavior.

Tales of Truth and Heartbreak

Not long after we returned to Santiago (by another truck for $2 CUP) we wandered around local neighborhood parks. As we stood in the shade figuring out what to do next, a friendly soft spoken local approached us. Like many local men, he was scrawny for his age, his dry, aged skin sagging on his brittle bones with gaunt fingers peeling due to overexposure in the sun. Seeing that we were competent enough in Spanish, he asked us if we could read in Spanish. I told him I could comprehend most of what I read in Spanish, with a bit of effort. He reached for a worn book from his bag, a book of Fidel Castro’s citations and speeches. He asked for our names, which he then proceeded to write a personalized message for us in the book. He handed us the book and asked us to take it as a gift, and told us firmly to read it. Knowing that Cubans don’t own much, we felt honored that a stranger gifted us one of his few possessions, and we felt obliged to sit with him longer. We were glad we did.

For the next thirty minutes or so we told him of our travels in Cuba, where we had been, where we were going next. He proudly told us that Santiago was the real Cuba, and not Havana. The music is better, he said, and the people are nicer.

But there are too many jineteros (hustlers), I replied.

His face grew solemn, the twinkle in his eye disappeared, and a frown replaced his smile. Because we are so poor, he immediately responded in anguish.

He spoke about the problem of prostitution in Cuba, where many 18-year-olds could be seen hand in hand with 60 to 70-year-old Canadians and Europeans. These women have children and $5/hour from a male customer would help them incredibly, especially since the average monthly salary in Cuba is $20. He talked about all the resources Cuba had—nickel, gold, coal, bananas, sugar, tobacco—but none are being used to the extent where the people could benefit. He talked about how the people were suffering from hunger, and he lifted his shirt to show us his ribs. At under 5′ and well below 100 lbs, his malnourishment was evident. He talked about how the rations and salaries from the government were not enough, and people had to do whatever they could to survive. He couldn’t blame the jineteros. And after that conversation, neither could we.

The next morning at a café, we were chatting with another fellow American traveler about the people of Cuba. She was practically fluent in Spanish, so she was able to have richer conversations with more locals. We learned that Cubans receive monthly food rations and salaries ranging from $14-$25, depending on the profession. Neither the rations nor the salaries were ever enough.

Next to our table sat another local, equally as scrawny and skinny as the man we spoke with the day before. His English was excellent, as he was an English teacher and was practicing his listening skills by eavesdropping on our conversation. He told us that as an English teacher, he made $14 per month. As part of the monthly rations, no one receives a sufficient amount of food or cooking oil, and to buy another bottle of cooking oil would cost $3. How could one spend $3 on cooking oil if one’s salary was $14? Chris offered to buy him a cup of coffee (which was only 20¢), and he graciously accepted. With his eyes clouded over with tears, he thanked us for sharing an English conversation with him, as small episodes such as that helped his day go by more easily.

***

Wow. Seriously, wow. In Santiago, we endured the painful logistics in Cuba by figuring out what it means to purchase domestic plane tickets and to rent a motorbike. Because we spent more than just a couple nights there, we had the time to really sit down with some locals to just chat about life in Cuba. And it was so painful. So heartbreaking. And it made things so much more clearer. We couldn’t fault the scammers, liars, and hustlers anymore. That is just what happens when people are desperate and must do anything they could to survive. Our 4 nights in Santiago brought a greater assimilation and understanding of the people and its country. My mind was further opened, and my heart further touched.